Vision-Language-Action, explained with a minimum of math and jargon

Want to really understand how Vision Language Action work? Here’s a gentle primer.

The promise of robotics has hovered just beyond our reach. We have masterful factory arms that assemble cars with millimeter precision, yet those same robots would be utterly lost if asked to perform a simple task like “clear the dining table.” The reason? The real world is messy, unpredictable, and chaotic—the exact opposite of a controlled assembly line. This gap between imagination and reality is the tension the industry continues to wrestle with.

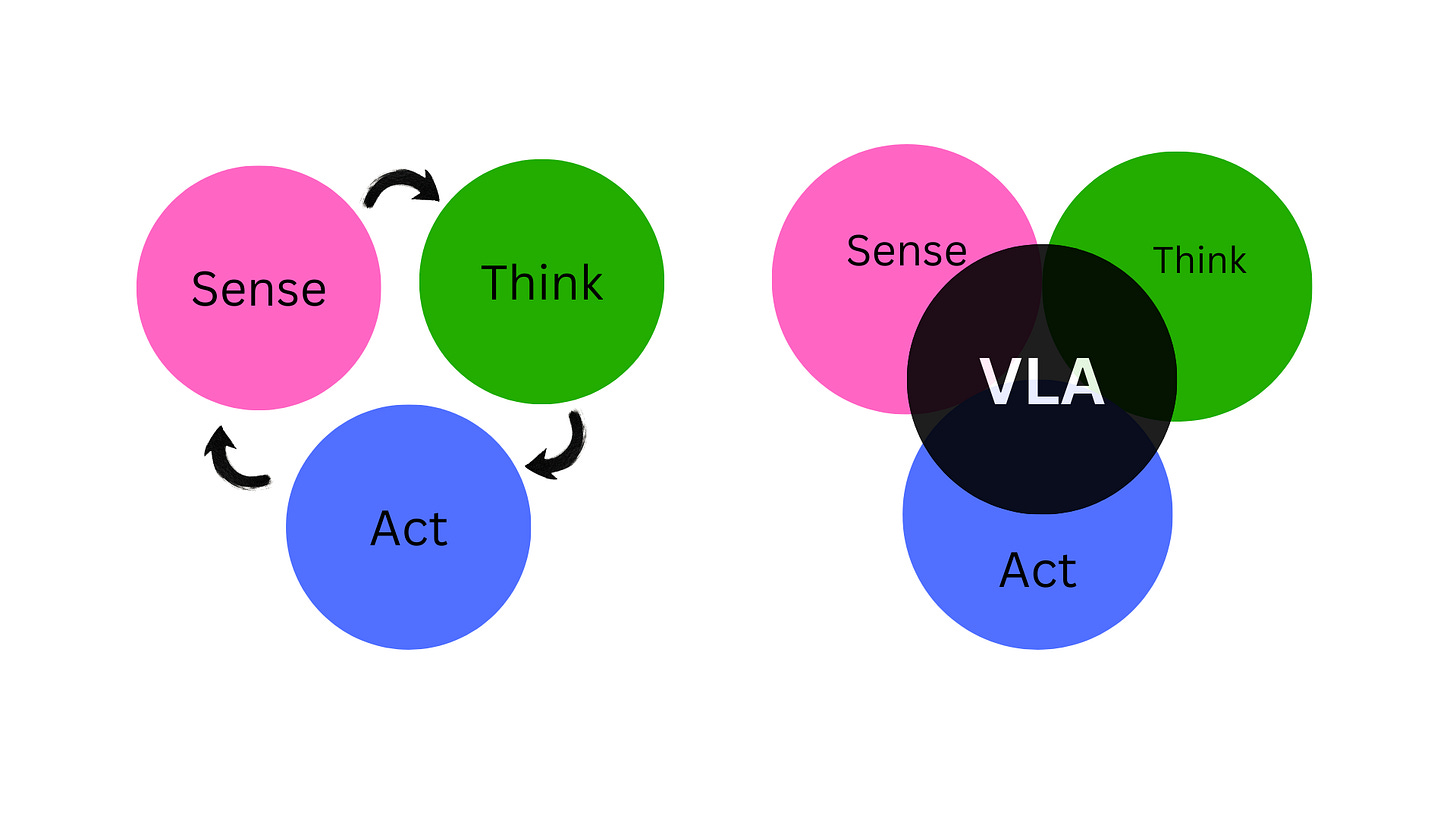

The breakthrough technology changing this landscape is the Vision-Language-Action (VLA) model. VLAs are a new paradigm that gives robots the ability to perceive our world through cameras, understand our requests in everyday language, and translate that understanding into physical action.

These models don’t treat perception, understanding, instructions and action as separate problems. They fuse all three into one system that sees, interprets, and acts.

Each piece works, but none share a common representation. The perception module has no idea what the instruction means. The planner doesn’t “see” the scene. The controller doesn’t understand why the user asked for the action.

Then vision-language models came along and showed impressive grounding: they could link words to objects, understand scenes, and follow natural language.

VLAs extend that ability all the way to robot actions.

They give a robot a single unified big model that can:

see the environment

understand what a human wants

produce actions that fit that context

This article will demystify VLA models by breaking down their three core components and explaining the main strategies used to build them. By the end, you’ll have a clear understanding of how today’s most advanced robots see, think, and act.

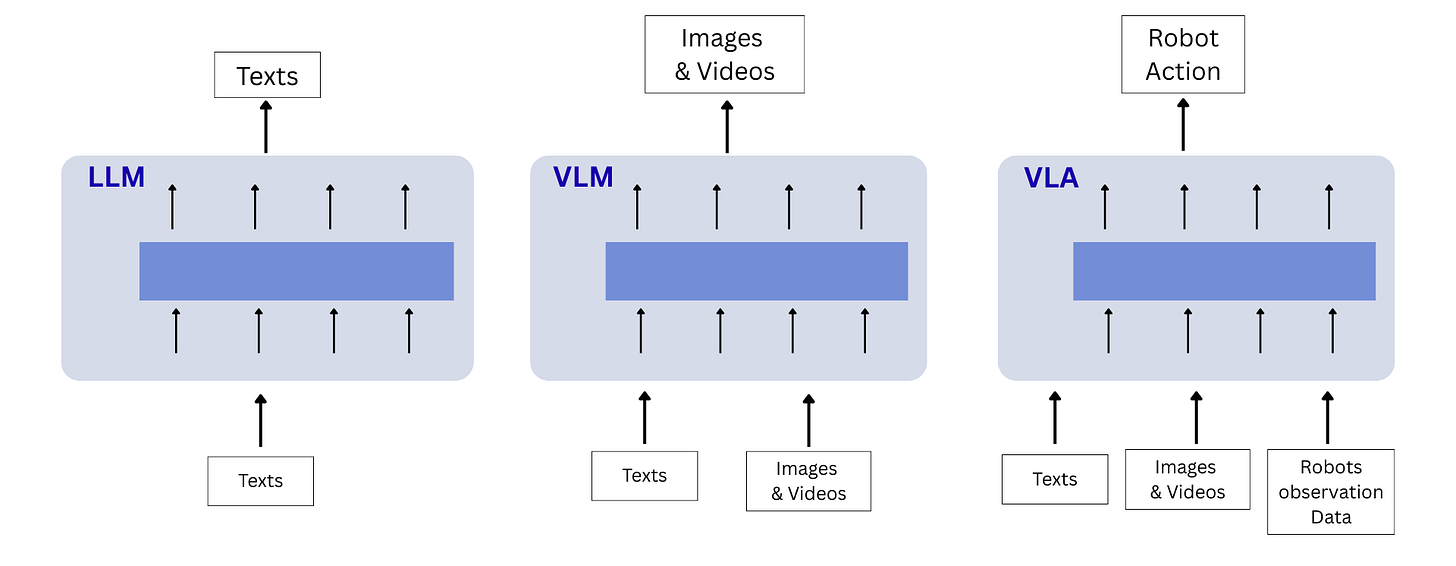

From LLMs to VLA?

LLM performs great for text-based tasks, but they lack and are limited by their understanding about physical constraints of environments in which robots operate upon. Also they generate infeasible subgoals because text alone cannot fully explain the end desired goal and a LLM doesn’t always describe delicate low level behaviors. However image or video can create fine-grained policies and behaviors.

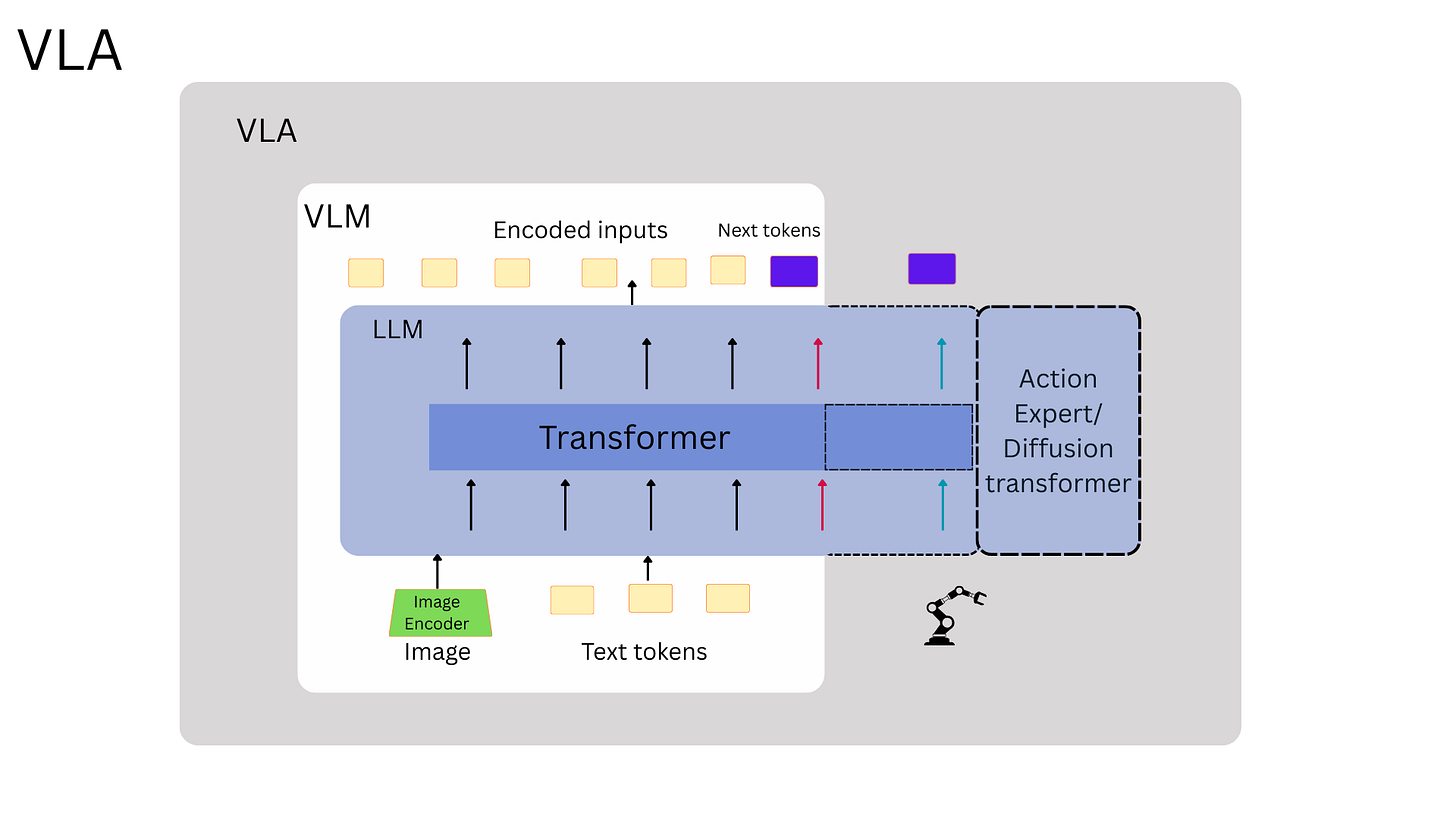

Vision Language Model has excellent generalization as they were trained on large multi-modal datasets of images and videos. For effective robotic control and manipulation having just VLM representations is not enough, action data matters. VLA extends VLM with an additional action and observation state tokens

It uses a powerful Large Vision-Language Model (VLM) to understand visual observations (what it sees) and natural language instructions (what you tell it).

It uses that understanding to perform reasoning that directly or indirectly leads to robotic action generation (what it does).

The secret to their intelligence lies in pre-training. The VLM at the core of a VLA is “pre-trained on vast web-scale image-text datasets.” Think of it like this: before ever controlling a robot, the model has already processed a huge portion of the internet. This gives it a deep, common-sense knowledge about objects, concepts, and how the world generally works. It’s the difference between a robot that only knows what a ‘cup’ is because it has seen 100 examples in a lab, and a robot that understands ‘cup’ in the context of coffee, kitchens, thirst, and fragility because it has processed millions of images and texts about those concepts online.

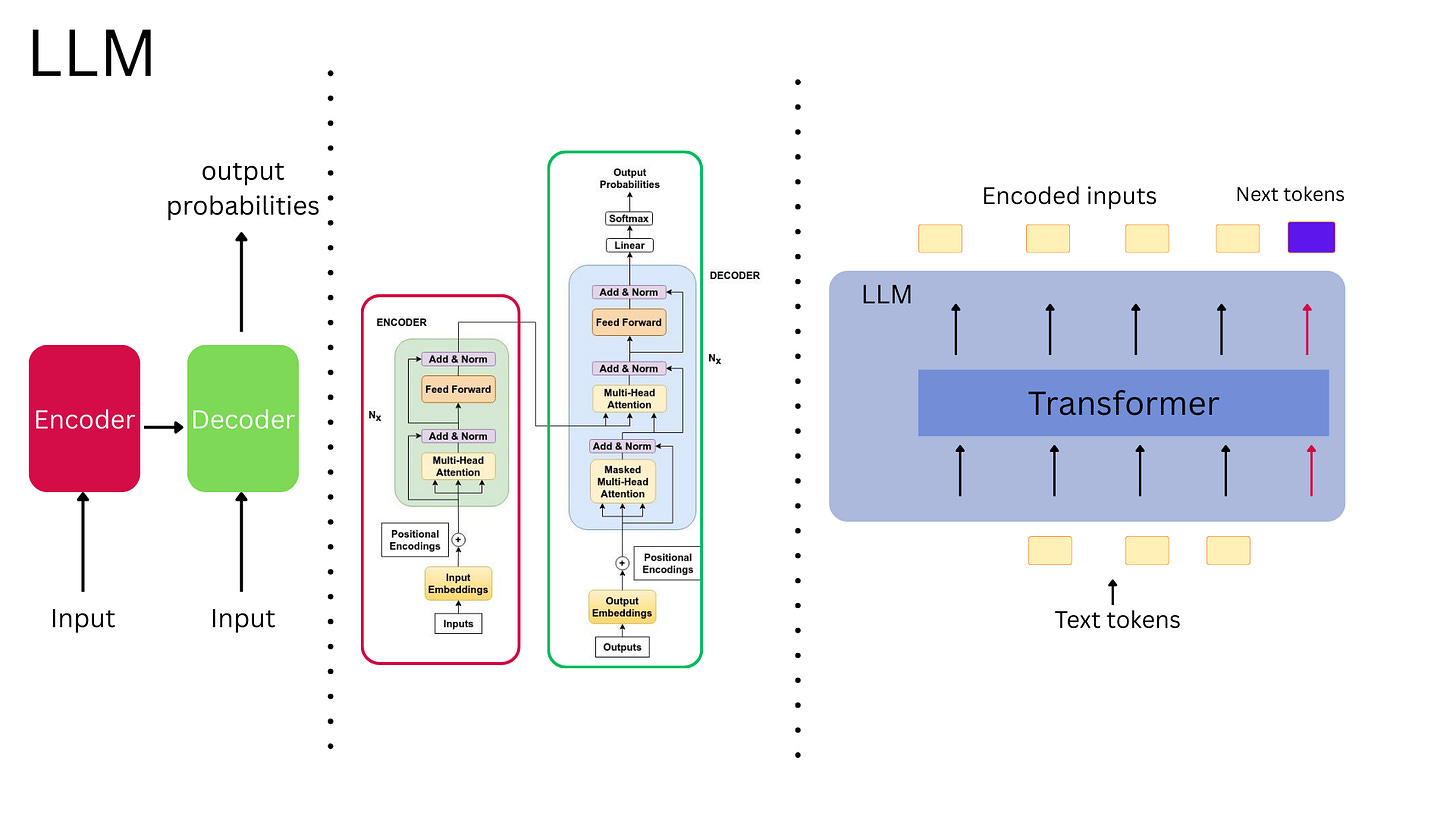

The architecture underlying modern LLMs, VLMs and VLAs is called the Transformer, introduced in a 2017 research paper with the fitting title “Attention Is All You Need.” This architectural breakthrough made today’s sophisticated language models possible.

The purpose of this piece is not to go into details about Transformers, but it is important to briefly mention that Transformer models are organized in layers, usually tens of encoders and decoder layers stacked on top of each other. Each layer contains attention mechanisms along with other components, and information flows through these layers sequentially. The interesting aspect is that different layers learn to extract different kinds of patterns.

This foundation gives large VLM-based VLA models four key advantages that older robotic systems lacked:

Open-world generalization: The ability to handle new objects and situations it wasn’t specifically trained on.

Hierarchical task planning: The skill to break down a big goal (like “clean the room”) into smaller, manageable steps.

Knowledge-augmented reasoning: The use of its vast pre-trained knowledge to make logical decisions.

Rich multimodal fusion: The power to seamlessly blend information from its vision and language senses to form a complete understanding.

Frontier VLA models attempt to do the aforementioned but may still have some deficiency in generalizing. But how do you build such a complex ‘brain’? Engineers have developed two fundamentally different ‘recipes’ to achieve this, each with its own philosophy about how a robot should think.

How a VLA represents the world

VLAs rely on a simple idea: convert everything—images, words, and robot motions—into long vectors of numbers called embeddings.

Once everything is in the same format, the transformer can process them together. Attention layers let them communicate.

a) Vision embeddings

A camera image is split into small patches.

Each patch becomes a vector representing features like:

edges

textures

shapes

object hints

spatial layout

This becomes the robot’s “visual language.”

b) Language embeddings

The instruction: “Place the red mug on the top shelf” is split into tokens.

Each token becomes a vector carrying object, goal, meaning and context.

c) Action embeddings

Robots operate with continuous values, but transformers use discrete tokens.

So VLAs convert actions into token sequences:

discretized end-effector poses

joint-angle bins

gripper commands

learned latent action codes

This simple conversion makes robot control predictable as a sequence. The model forms an internal, grounded understanding of what needs to happen next.

d) Grounding

The model links:

“mug” → the object

“red” → the correct instance

“top shelf” → the target region

e) Action prediction

It produces either:

a sequence of action tokens

a trajectory

intermediate plans (subtasks/waypoints)

f) Execution

The robot converts tokens into joint targets and gripper commands.

You get real motion.

How VLAs generate action: Recipes for Robot Intelligence

To understand the two main ways to build a VLA model, let’s use an analogy from the kitchen. Imagine an expert chef who can instantly see an order, know what to do, and start cooking in one fluid process. This is like a Monolithic model. Now, imagine a head chef who first writes a detailed recipe (the plan) and gives it to a line cook (the policy) to execute each step precisely. This is like a Hierarchical model. This choice represents a fundamental engineering trade-off between the reactive speed of a monolithic system and the deliberate, interpretable planning of a hierarchical one for more complex tasks.

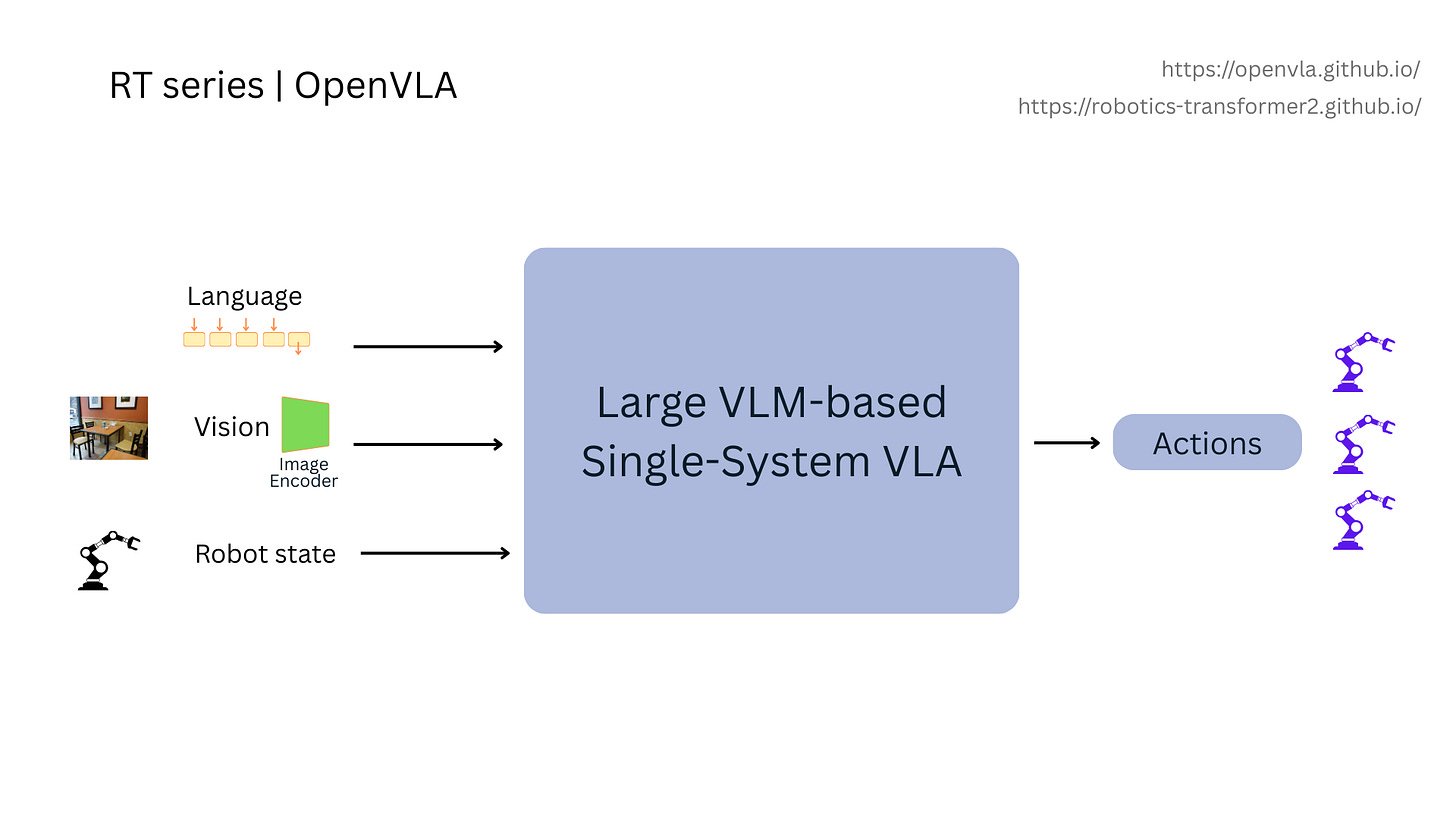

i) Monolithic Models: The All-in-One Expert

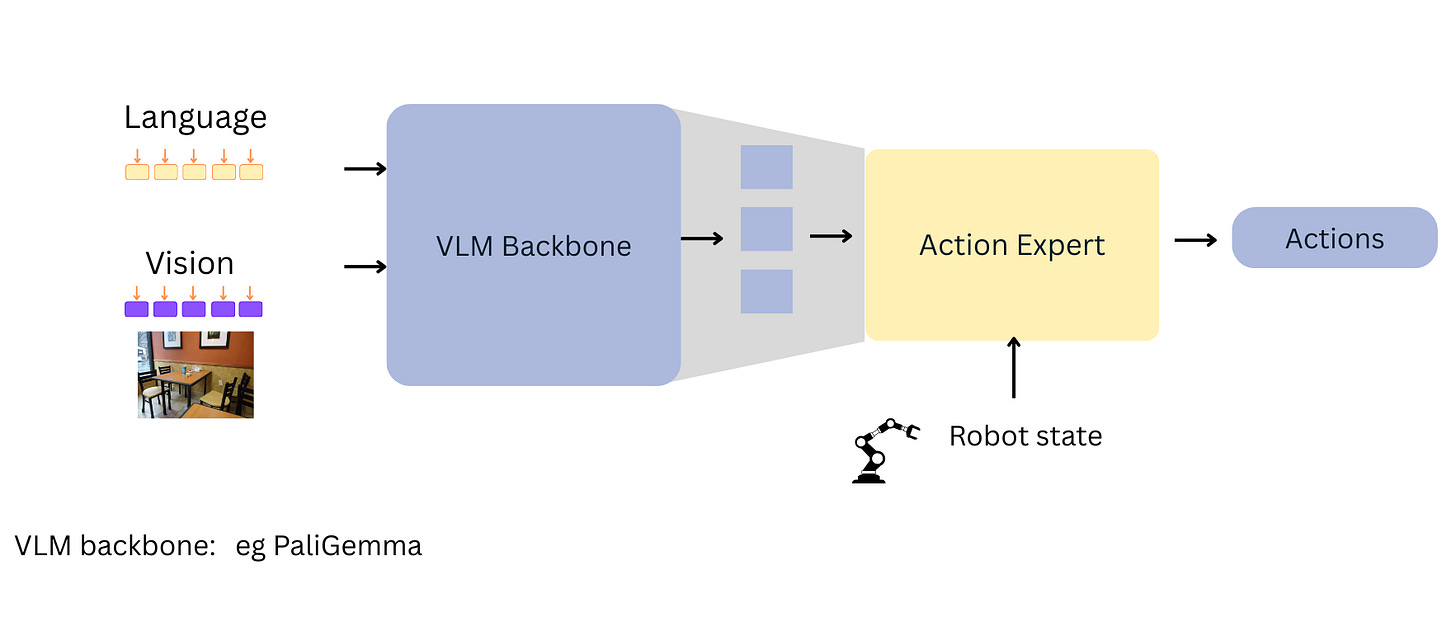

Monolithic models integrate vision, language, and action into a single, unified architecture. While some designs use one massive neural network, others use a dual-system approach with a large ‘reasoning’ module and a faster ‘action’ module that work in tight coordination. In either case, they are designed to translate a high-level instruction directly into low-level robot actions.

A groundbreaking example of this is the RT-2 model. Its key innovation was to treat robot actions as text tokens that are included in the same training corpus as normal language outputs. This means the robot’s movements—like ‘move gripper to coordinate X, Y, Z’—were converted into a text-like vocabulary. These ‘action words’ were then mixed in with the vast web-scale image and text data the model was trained on. This simple but brilliant trick allowed the model to learn about physical actions as if it were just learning another language, directly connecting its web-knowledge to real-world control.

Models like RT-1, RT-2, and OpenVLA predict the next action token auto-regressively step by step.

“move down → close gripper → lift → move → place”

They do this By discretizing the robot’s continuous action space into a token sequence, the model can sequentially predict action tokens. The VLM component will receive the image/video observation, natural language instruction, and robot states as input. Then it will autoregressively generates action tokens, which can be converted into exe cutable actions through a downstream de-tokenizer

In monolithic dual systems, one module handles slow, semantic reasoning.Another handles fast, reactive control. They exchange information so the robot can think and respond. The other approach common especially in dual systems is Diffusion or flow-matching trajectories

The action expert use Diffusion model which are trained via adding progressive adding noise to a sample and then asking a network to denoise it. During generation, we start with noise and progressively denoise it. In short, they generate a full trajectory by refining noise into smooth motion.

This often produces better grasps and stable paths.

Another very recent work worthy of mention is pistar0.6 which trains a Reinforcement Learning RECAP to critic or coach the VLA model. When the robot makes mistake in any given task, the value function (which is another AI model) score drops. The critic calculates an “advantage” score—a simple indicator of whether that action was better or worse than average. The main policy is then trained to perform actions that earn a “positive” advantage from its critic. This makes the robot learn from his own experience and get better over time

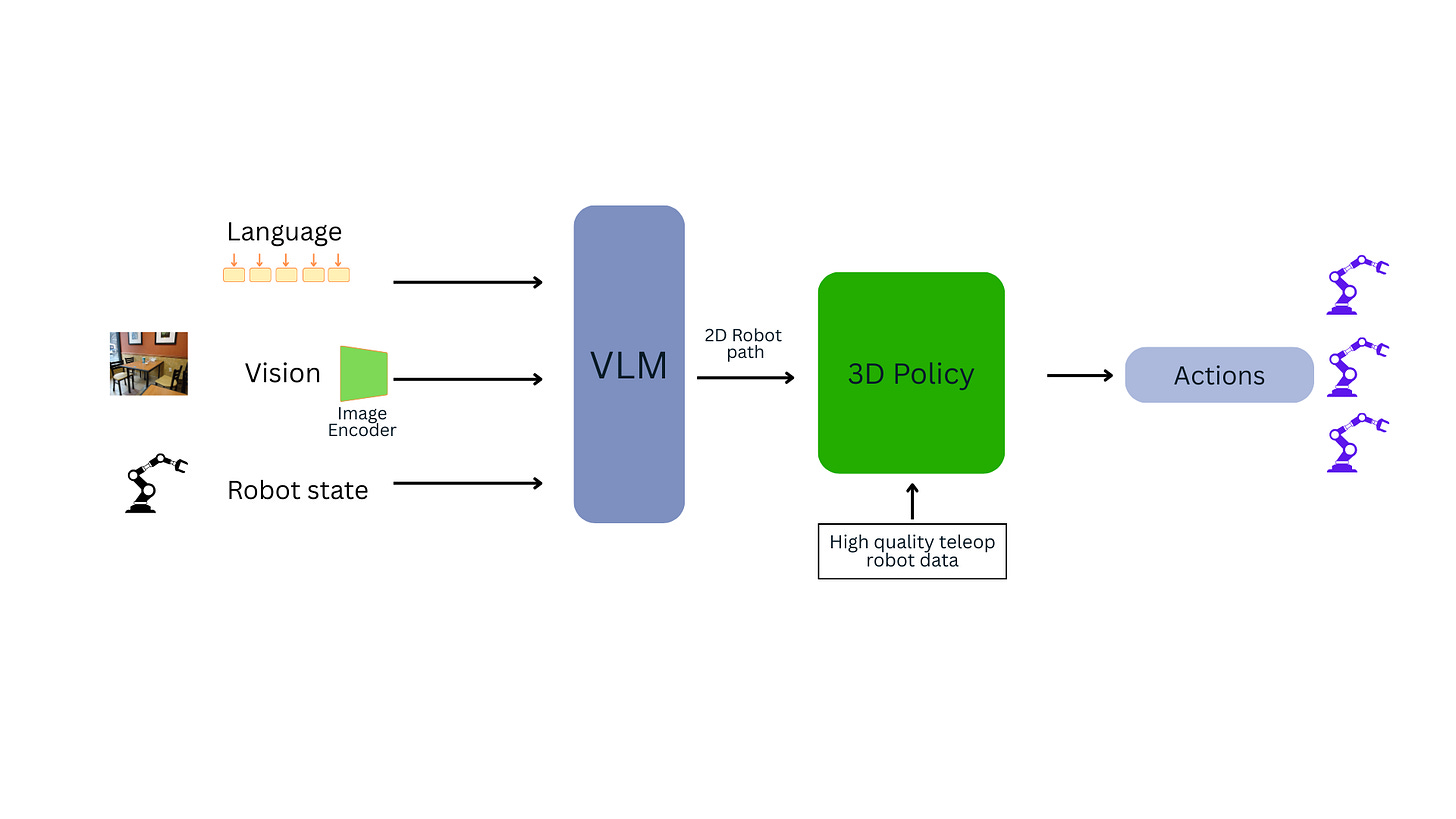

ii) Hierarchical Models: The Planner and the Doer

Hierarchical models take a different approach, seeking to “explicitly decouple planning from execution via interpretable intermediate representations.” This means the system has two distinct jobs handled by separate parts:

A high-level planner (the “brain”) that receives the instruction and creates a plan.

A low-level policy (the “hands”) that executes the plan.

These generate:

subtasks

keypoints

mini-programs

waypoint sequences

A controller turns these into motions.

It helps with long, multi-step tasks.

Examples of Hierarchical models include: HAMSTER, RT-H from Google DeepMind Robotics and Stanford University, MoManipVLA, HiRobot and many other more.

The crucial difference is that the planner first creates a human-understandable intermediate step before any action is taken. This output makes the robot’s decision-making process transparent and interpretable. The plan could be:

A list of subtasks (e.g., 1. pick up sponge, 2. wipe table, 3. throw away sponge).

A set of keypoints (e.g., specific coordinates on a drawer handle to pull).

A simple program or script for the robot to run.

Affordance maps (e.g., highlighting which parts of an object are graspable).

This separation makes hierarchical models excellent at handling long, complex, multi-step tasks. It also makes it easier for developers to understand why the robot is doing what it’s doing, which is critical for debugging and safety. Different architectures do this differently, but four patterns dominate.

How VLAs are trained

Training a VLA is teaching the model a single mapping:

what it sees → what the user wants → what action should occur next

VLAs learn from three types of data.

a) Web-scale image–text data

Teaches object recognition and scene understanding.

b) Robot demonstrations

This is where physical skill comes from.

A demo is a sequence:

images

an instruction

actions

c) Synthetic or simulated data

Useful for variations, edge cases, and long tasks.

NVIDIA OpenUSD , Omniverse and Isaac Sim allow to generate synthetic data. Using Gr00t Mimic, we could also generate synthetic data by only providing few samples of actual robot demonstration data. World Labs, a new research lab/startup by Prof. Fei Fei Li also allows to generate synthetic 3D environments useful for training robots from text descriptions.

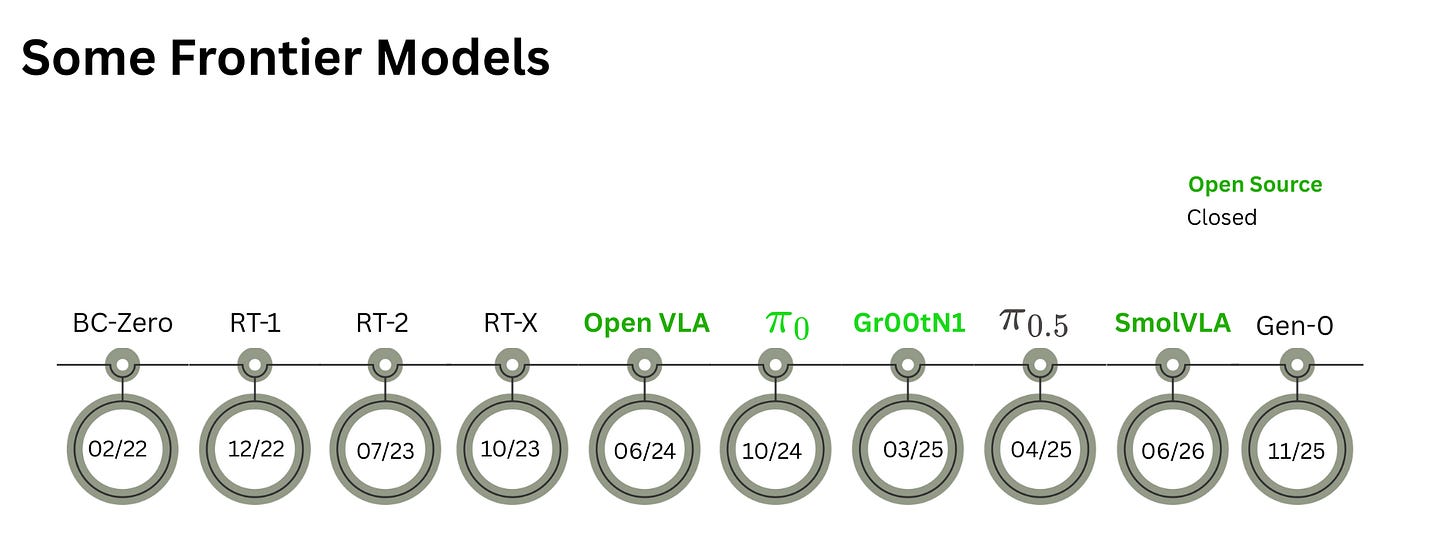

Examples of robot learning datasets used are Bridge Data2, The Distributed Robot Interaction Dataset (DROID) , OpenX Embodiment, etc. Datasets used in some other works are closed and not publicly available like in Gen-0

The training loop itself

For every demonstration:

Encode images

Encode instructions

Feed in robot state

Append action tokens

Hide future actions

Predict the next action token

Adjust weights

Repeat across millions of tokens

Over time, the model learns patterns:

which objects matter

how tasks unfold

how to generalize beyond the demos

how language maps to motion

VLAs don’t memorize scripts. They learn the hidden structure.

What a well-trained VLA can do

A trained VLA quietly develops skills like:

grounding instructions in a scene

picking relevant objects

stabilizing trajectories

chaining subtasks

adapting to unseen objects

recovering from small errors

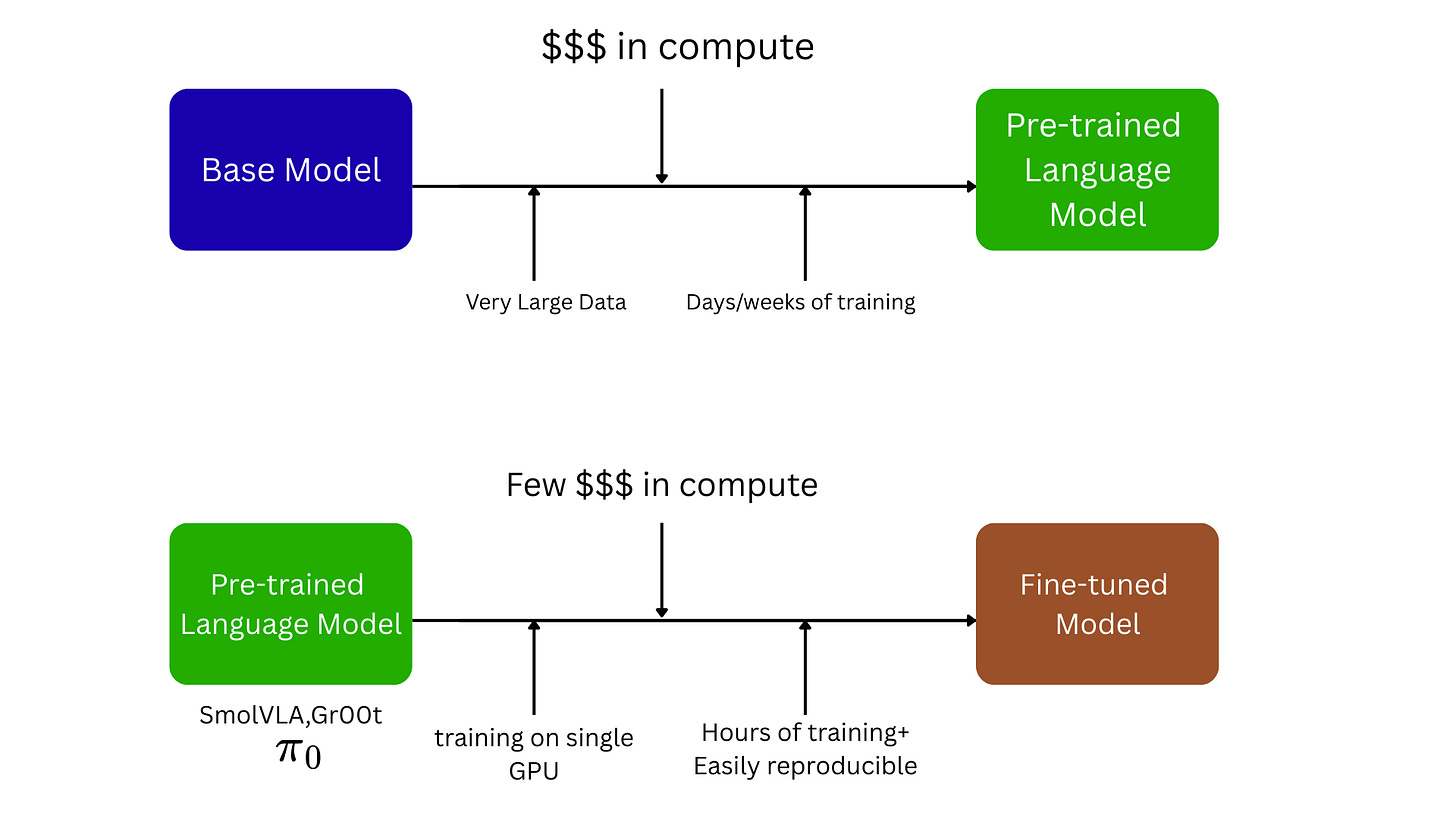

These skills emerge because the model sees them repeatedly in real demonstrations. This (pre) training is usually done on very large amounts of data. Therefore, it requires a very large corpus of data, and training can take up to several days/weeks/months.

Fine-tuning

You don’t need to train a huge model from scratch.

Many teams:

pick a pretrained VLA

gather a small dataset (300–3,000 demos)

use LoRA to fine-tune

train for 2–12 hours

test and iterate

Lerobot is democratizing this for robotics by making it possible to purchase a $200 robot , collect data, train on open source models like Gr00t, SmolVLA, ACT, and pi. and then fine-tune your robot on specific tasks

This adapts the model to your robot, tools, lighting, and tasks.

Fine-tuning uses a pre-trained model, such as SmolVLA, Gr00T, OpenVLA, as a foundation. The process involves further training on a smaller, domain-specific dataset. This approach builds upon the model’s pre-existing knowledge, enhancing performance on specific tasks with reduced data and computational requirements. Fine-tuning transfers the pre-trained model’s learned patterns and features to new tasks, improving performance and reducing training data needs. It is already popular in NLP for tasks like text classification, sentiment analysis, and question-answering and is equally very popular in testing things out in Robotics VLA tasks .

Where VLAs still struggle

VLAs are powerful, but not perfect.

Common issues:

mis-grounding in clutter

drifting on long tasks horizons

hallucinating objects

unstable contact-rich manipulation

latency with large models

high compute cost

limited interpretability

These limitations are active research areas and some have existing solutions from different research labs.

Conclusion

Vision-Language-Action models represent a transformative shift in robotics, moving the field away from rigid, pre-programmed automation and toward flexible, language-driven interaction. By leveraging the vast knowledge of pre-trained VLMs, these models empower robots to understand and act in the human world with unprecedented intelligence.

The journey is far from over. The future isn’t just one intelligent robot, but teams of them collaborating (multi-agent cooperation) on complex jobs, seamlessly navigating our world while performing intricate tasks (mobile manipulation). And to get to this point, robots as embodied AI need to understand the world not only in 2D but in 3d and 4D and have spatial intelligence. AI can analyze a picture, answer questions about the, excel at reading, writing, summarizing, identifying patterns. But the world is more than language and not 2D. Same Generative AI struggles with estimating distances for instance, cannot navigate mazes, drive our cars or guide robots in home or work collaboratively like in an emergency scene. All these require deeper spatial understanding of the world. Success in this will help robots eventually become smarter

Hi, Hafeez Jimoh is a Robotics Instructor at Lawrence Tech University. This is the Robotics FYI newsletter, where I help readers better understand important topics in Robotics. If you like the newsletter, please subscribe, share it, or follow me on LinkedIn!

Super interesting article, thank you for sharing it. Actually, I’m thinking of doing a PhD in robotics & AI but not too sure where I’d wanna do it in. I’m thinking this VLA field might be it!! I recently started my master’s in robotics and in the first week, we were shown that exact diagram, that shows the flow of information between perception, path planning and control, and I remember thinking to myself, how can I be involved in all 3? I don’t wanna just pick one and specialise in that. This VLA work perfectly brings all of that together👌🏿It’s also new and looks to have lots of problems that are yet to be solved. You know of any research labs I could look into that are doing this work?

Solid breakdown on VLAs, especially the monolithic vs hierarchical distinction. The chef analogy worked well. What strikes me most is the embedding unification trick, turning vision, language, and actions into a common vocabulary that transformers can process end-to-end. I've seen this sameidea in multimodal LLMs but extending it to robotic control feels like crossing a different threshold entirely. The tokenization of continuous motor commands still seems like the trickiest part to me, wonder if we're gonna hit ceiling with discretization or if diffusion-based approaches will scale better for contact-rich tasks.